Environment and Nature in New Zealand April 2009

The Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House

Walter Cook

Large architectural statements in a formal classical tradition are rare in New Zealand. In Wellington, when these were planned, they were often left unfinished. There are the Carrillion and the Dominion Museum on Mount Cook. Both were designed in 1929, and built between 1930 and 1936, set in formal terraces planted with pohutukawas and other native trees. Two thirds of the museum building was completed, and the formal ceremonial way connecting the complex to the central city never became more than a pipe dream. Then there is our national Parliament Building. Designed in 1911, only half was built between then and 1928, giving the parliamentary complex its distinctive appearance – a cluster of half finished buildings dating from 1899 to the 1970s. Like fault lines in the Wellington landscape, this group of buildings seems to reflect disjunctions in our cultural and political history when the country took sudden new directions that rendered architectural projects redundant in the middle of construction. In this case the classical baroque style of the Parliament Building was not reflected in the layout of the grounds.

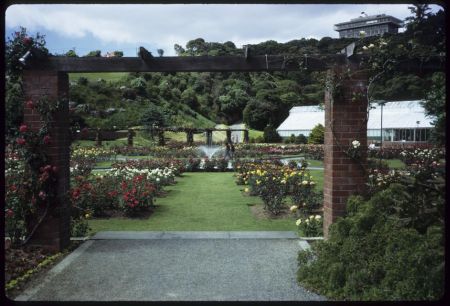

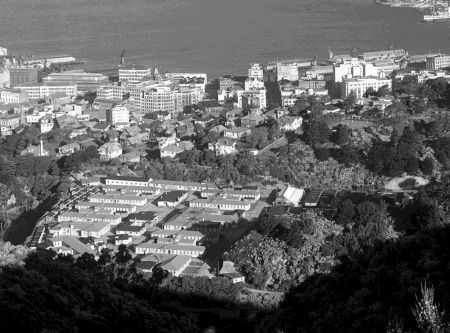

On the other hand there are two projects that were completed. One is the Wellington Railway Station that opened in 1936. Its great hall is an architectural experience like no other in the country, except, perhaps, for the interior of the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Christchurch. The entrance hall’s vaulted ceilings refer to the baths of Carriculla in Rome and were designed as a fitting gateway to the city in the days when rail was the main form of public transport. Today its gigantic monumentality, like the opening section of Alfred Hill’s Ceremonial Ode, is probably seen as a magnificent “one off” aberration – something totally un-New Zealand in character. The building fronts a formal forecourt of lawns planted with pohutukawas. The other example of a completed project in a formal classical tradition is the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House. This article examines the construction of the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House. (Fig 1)

Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House

For many people, the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House are their first contact with the Wellington Botanic Garden. With their horticultural displays, restaurant, and accessibility they have always been a hit with tourists and the local public. Even during the 1960s and 1970s when the Botanic Garden as a whole was not heavily used, people still flocked to the Rose Garden and Begonia House, especially on Sunday afternoons.

Fig 1: Lady Norwood Rose Garden, 1975. Photo – Donal Duthie. Alexander Turnbull Library reference PA12-1779-5.

The plan for this complex of gardens was most likely the work of the Director, Edward Hutt. It was certainly the largest addition to the Botanic Garden established during his directorship (1947-1965). (Fig 2)

The scheme was expressive of a forceful new director, and a community moving to reclaim its open spaces, many of which had been appropriated by the military during the Second World War. It was also expressive of an affluent post-war Parks Department, which, compared to the 1920s and 1930s, had money to burn. In 1965, at the end of Hutt’s reign, Wellington had the best funded parks department in the country.

On becoming director in 1947, Hutt wasted no time in reorganising the department and getting new projects up and running. That year the new plant nursery at Berhampore was built. This operated as a factory ultimately pumping out millions of bedding plants for use in the Botanic Garden and throughout the city. It was also where trees and shrubs were grown on, until in 1956 this function was relocated to an open ground nursery at Makara.

For many people, the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House are their first contact with the Wellington Botanic Garden. With their horticultural displays, restaurant, and accessibility they have always been a hit with tourists and the local public. Even during the 1960s and 1970s when the Botanic Garden as a whole was not heavily used, people still flocked to the Rose Garden and Begonia House, especially on Sunday afternoons.

Fig 2: Edward Hutt and his long-serving chairman of Parks and Reserves, Dame Elizabeth Gilmer photographed in the Botanic Garden in 1952. Alexander Turnbull Library reference ½-020495-F.

At the Botanic Garden, Hutt extended seasonal features such as spring tulip displays which at their most extensive consumed between 70 and 100 thousand bulbs, though some of these were also used in city plantings. Throughout the 1950s he tidied up the Main Garden by installing stone walls, and establishing the present Camellia and Peace gardens.

Roses in the Botanic Garden

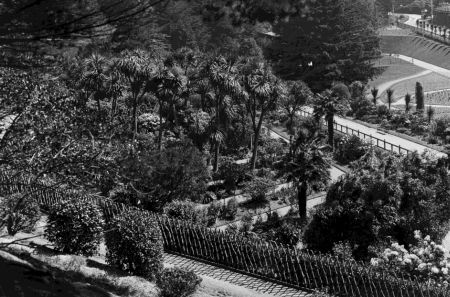

After Berhampore Nursery, a Rose Garden and conservatory were his next big horticultural project, and in July 1948 the plan for these was published in The Dominion newspaper. Roses do not seem to have featured in the Botanic Garden of the Board (1869-1891) in the way that camellias and rhododendrons were. What James Hector, Wellington Botanic Garden’s first Director, did establish in the 1870s was a teaching garden on the site of the present Sound Shell Lawn. (Fig 3) The layout of this garden, with its formal rectangular beds, was to become the basic structure of the first Rose Garden in the Botanic Garden. The Teaching Garden remained unchanged after the City Council took over the Botanic Garden in 1891, and remained unchanged until well into the 1900s. Photographs of the cleared, newly planted Main Garden dating from circa 1906, show that it was still intact at that date. Other photographs dating from circa 1906 to circa 1910 show that at its southern end, some of the rectangular beds had been modified, and were used for displays of seasonal annuals.

Fig 3: James Hector's Teaching Garden, Wellington Botanic Garden ca 1910. Photo – S C Smith. Detail of Alexander Turnbull Library reference 1/1-020191-G.

The transformation to a Rose Garden was gradual. Rectangular beds were divided by new paths and much of the original planting including cabbage trees was retained. That roses featured in the garden by 1912 is recorded in a report to the Town Clerk from Superintendent Glen stating that the “Enclosed Garden “had been broken into and that roses and other flowers had been cut and strewn about.” By 1917 the garden had become “The

Rosary,” though many of Hector’s original plants still remained. The last of Hector’s cabbage trees and rhododendrons were finally removed in 1928, at which time the area was a fully fledged rose garden. The beds were edged with clipped box, and were underplanted with flowering annuals such as pansies and violas, a practice introduced in Britain in the late nineteenth century, by the horticultural writer and gardener, William Robinson, a doyen of the so-called “natural garden”. The old Rose Garden remained until the Lady Norwood Rose Garden was completed in 1953. I don’t know when it was finally grassed over, but it was still alive and well in 1951.

The site of the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House

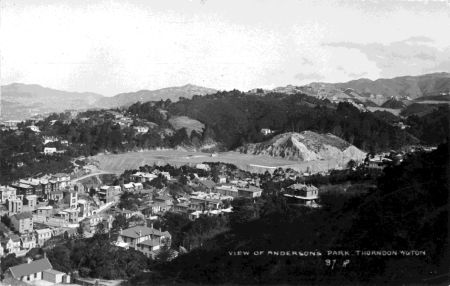

The site occupied by the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House is the result of the most drastic landscape modification ever inflicted on the Botanic Garden. Originally, a valley extended from the bush at the back of the Dell, through the site of Anderson Park and Bowen Street, and included Sydney Street. On the western side, the Herb Garden ridge was higher, and ran above the site of Anderson Park, connecting with the ridge in Thorndon on the eastern side of Tinakori Road. (Fig 4)

Fig 4: Honeyman’s Gully, Thorndon, Wellington looking north, ca 1880. Taken from above the site of the present Begonia House. Photo – Henry Whitmore Davis. Alexander Turnbull Library reference ½-230699-G.

Part of this land had belonged to the Weslayan Church, but had been transferred to the Botanic Garden in 1872. The rest was cemetery reserve, unused, and planted by the Botanic Garden board. In the late 1870s the valley was crossed by a high embankment that carried Glenbervie Road, the predecessor of Bowen Street. By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this area along with the Botanic Garden, was being surrounded by new suburban developments. Kelburn to the south, Northland to the West, and infill housing on the town acres along Tinakori Road increased the western residential population enormously. This boom in local population, combined with the development of organised sports, made the long projected Thorndon recreation ground politically achievable. The valley was chosen as the site for what became Anderson Park, one of a flush of sports grounds constructed in Wellington between 1905 and 1910. The others were the completion of Kelburn Park, Duppa Street (now Wakefield Park), and Kilbirnie Park.

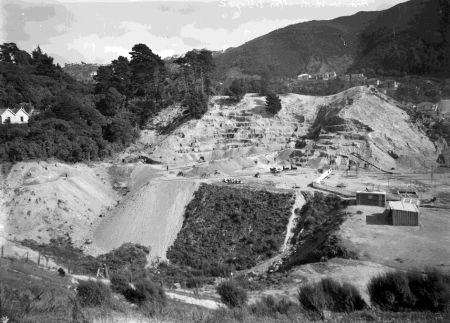

The building of Anderson Park began in 1906 and was completed in 1910. Its construction involved the demolition of part of the western ridge, which was subsequently used to fill the valley. The money available for this project did not allow for filling that part of the valley on Botanic Garden land. This remained a gully, used as a rubbish dump by the Botanic Garden until the great depression of the early 1930s. (Fig 5)

Fig 5: Anderson Park, newly completed, 1910. Alexander Turnbull Library reference PAColl-4601-01.

Unemployment resulting from the depression brought a “work for the dole” response from the Forbes/Coates government (1931-1935). This resulted in a number of work relief schemes, the most important of which was scheme five. Under this scheme the Government supplied the money, and local bodies the jobs and tools. Wellington benefited hugely from work done by cheap, subsidised labour. Sports fields multiplied, new roads were built and old ones widened, and much of the Town Belt was planted. One of these work relief schemes was the Anderson Park extension. Between 1931 and 1934 much of the remaining western ridge was demolished and thrown into the gully, providing a site, first for a sports field, then from 1942 a military transit camp, and finally the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House. (Fig 6. Fig 7)

Fig 6: Construction of Anderson Park extension, Wellington Botanic Garden, 31 March 1932. Photo – The Evening Post. Alexander Turnbull Library reference EP-2485-1/2-G.

The civic Rose Garden project

The Parks Department’s files on the rose garden, the Council minutes, and the Parks and Reserves Committee’s minutes from late 1945 to 1948, contain no information, or hint, of discussions about, or lobbying for, a Rose Garden and Begonia House. The Parks Department file on the Rose Garden begins after the proposal had been accepted, and the plan published in The Dominion on 15 July 1948. Nor is it clear who came up with the idea for a Rose Gardenand Begonia House, or who designed the layout.

Fig 7: Anderson Park military transit camp, 1944. Photo – William Hall Raine. Detail of Alexander Turnbull Library reference ½-100724.

According to Hutt’s successor, Ian Galloway, this was likely to have been Hutt himself, and all the evidence that I have found so far, seems to support this conclusion. Hutt had trained in England and Scotland in the commercial nursery firms of Henry Cannell and Son, Swanley, Kent, and Dobbie and Co. of Edinburgh. Personal documents, now in the Council archives, include information that while in Edinburgh, he took a course in landscape and garden design. With these documents there is also a plan for the layout of gardens around Lower Hutt’s Civic Centre, drawn up by Hutt when he was Director of Parks and Reserves in that city, before taking the Wellington job. These demonstrate that he was quite capable of designing a layout like the proposed Rose Garden and Begonia House.

Other records in the Council archives also imply that Hutt was the probable author of the plan. He began his directorship in February 1947. That month he produced a report detailing a plan for the reorganisation of the department. It begins with comments on the organization of the Director’s office. It has no adequate filing system. Nor is there evidence “of any landscape plans for the development of parks and reserves.” Those plans that were on-file referred only to the engineering side of development. As a result of this, one of his recommendations was that any future development of parks and reserves should involve the preparation of detailed plans for their layout, and that these plans should be the responsibility of the Director. To date I have not had the time to look into the records to see whether there are collections of plans dating from 1947 onwards, the existence of which may reveal or add weight to the contention that Hutt himself designed the layouts, as he seemed to recommend in his report.

Another record that suggests he did, or at least oversaw their preparation, comes from a recommendation he made to Council in 1957. Hutt wanted to employ a landscape architect because the planning and design of parks and reserves were now the responsibility of the Director of Parks. Previously such work was done by the Engineers Department. Because the Parks and Reserves Department had grown over the previous ten years, the Director’s role had become more of a political and administrative job than before. This request had no outcome, and the Department was not to get its first landscape architect until the late 1960s. From all this it seems to me probable that in 1948 Hutt was the person who conceived, and probably drew up the concept of the layout of the Rose Garden and Begonia House, which he then handed over to a surveyor and draughtsman.

It took two years from 1946 to remove the military buildings on Anderson Park and on the site of the future Rose Garden and Begonia House. This involved negotiations with the Government around whose responsibility it was to meet the costs and do the work of restoring reserves taken by the military during the war. In some cases a trade-off was reached by which the Council agreed to do the work, and in return was allowed to keep the buildings. This is what happened in the case of Anderson Park and its extension. After the war, timber was in short supply, and timber from the military buildings was used for housing,particularly for foremen and custodians of parks and reserves. Acute labour shortages during the late 1940s and into the 1950s meant that free or low rental housing with a job encouraged staff retention.

The removal of concrete foundation slabs from Anderson Park and the Park’s extension began in November 1947, which probably means that the area was not finally cleared until well into 1948 or 1949. Another factor of the post-war cleanup and refurbishment of reserves was the amount of money available for the task. At its meeting of 1 July 1946, Council proposed two loans that were subsequently approved in October. One of £96,000 was for the improvement of city reserves generally. The other of £16,400 was specifically to restore the playing fields at Anderson Park. This suggests that, other than to return the grounds to their pre-war uses, there was as yet no plan to develop a Rose Garden or a Begonia House.

Money for improvements to Wellington’s reserves kept coming in the late 1940s. In 1949 a loan of £180,000 was authorised for 1950. Again there is no mention of money specifically for the Rose Garden project that had already been approved. Thus, the cost of the project may have been seen as part of the post-war refurbishment, and was embedded in these loans. One area that I have not had time to hunt out in relation to this are documents relating to establishing the scope of council estimates in the late 1940s.

The first reference to a Rose Gardenand Begonia House comes from the Reserves Committee’s minutes for 5 July 1948. At this meeting “the Director submitted a plan for the development of Anderson Park and the northern portion of the Botanic Garden to provide for two hockey grounds, or one rugby ground at Anderson Park, and for a children’s play area, a rose garden, a winter garden, Begonia House, and fernery.” The plan as submitted was approved and later endorsed at the Council meeting on 14 July 1948, the day before it was published in The Dominion. It would appear that any discussion about the project, or directive to Hutt from his committee to come up with a plan, took place outside meetings, and off the record. (Another source that I have not searched in relation to this is the Wellington newspapers.)

Judging from the Rose Garden file, in July 1948 Hutt was already thinking about the planting of the new rose garden. He intended to use species as well as horticultural rose varieties. To this end on 16 July 1948 he wrote to the directors of Kew and Edinburgh Botanic Garden asking for seeds of rose species. Edinburgh sent seed, and Kew promised to do so the following season. I have found no documentation indicating that plants resulted from this, or that species roses ever became part of the original Rose Garden plantings. On the other hand, the file contains sheaves of letters and lists to and from New Zealand nurserymen relating to the purchase of rose varieties. The building of the Rose Garden did not get underway until 1950, and was still at a rudimentary stage in March that year when a photograph of the area was published in The Evening Post on 10 March 1950. (Fig 8) The caption with the photograph reported that Anderson Park would finally be ready for rugby league games during the coming winter season.

Fig 8: Lady Norwood Rose Garden under construction, 10 March 1950. Photo – Evening Post. Alexander Turnbull Library reference 114/123/12-F.

Judging from the orders for roses in 1951, planting must have begun in 1952. This continued in 1953, with the added urgency that the garden be completed in time for the royal tour that year. To shelter the new Rose Garden from north-westerly winds, its northern half was surrounded by a manuka brush fence.

Later a border of large shrubs was planted along the Anderson Park boundary for the same purpose. In planning the rose garden, Hutt was supported by the Wellington Rose Society. In 1949 the Society held a rose festival that raised £147, 15 shillings and 2 pence for the garden, and gave the department 100 rose bushes. Given that the weekly wage of a gardener in 1949 would have been around £3, in present value, this was not an insubstantial sum of money. This donation does indicate community support for the Rose Garden project. Hutt and his predecessor, J.G. MacKenzie, worked at a time when horticulture in Wellington, and the development of city reserves attracted a fairly high level of community interest. This was expressed in organisations like the Wellington Horticultural Society, the Wellington Beautifying Society, and other specialist organisations such as the Rose Society. The Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House in the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s, realised this interest through the support of a project that embellished the garden and the city, and which represented the large-scale achievement of an horticultural ideal.

Lady Norwood and the Norwood Family and project completion

At this point I want to examine the connection of Lady Norwood and the Norwood family with the new Rose Garden and Begonia House. (Fig 9) Hutt’s predecessor, J.G. Mackenzie, made two attempts before the war, and one during the war, to build a winter garden. When he failed in his bid for this in 1939, Lady Norwood donated £200 to improve the old Begonia House that doubled as the main propagating house located at the Botanic Garden nursery. In 1949 she donated a further £300 towards the Begonia House projected in Hutt’s plan. This seems to be the beginning of the financial support underwritten by the family, support that ultimately enabled the completion of the project, and allowed for the landscaping of the surroundings. In 1950 the City Council decided that the new Rose Garden would be named after Lady Norwood, and in 1955 she offered to donate a fountain. This was installed and was operational by 12 November 1956. Lady Norwood’s fountain was replaced by the present one in 1977, donated by her children.

Sometime during the first decade of the Lady Norwood Rose Garden’s existence, there was a great disaster. A gardener accidentally sprayed the roses with 24D, a hormone herbicide, mistaking it for liquid DDT, and killed all but two beds of roses. All the bushes were removed, and that season the garden was planted with annuals until a new batch of roses could be installed. Needless to say I have found no documentation relating to this event in the City Council Archives, but it was still one of the horror stories related by staff when I began my apprenticeship at the Botanic Garden in the early 1960s. Here again newspapers may hold information. I was told that no staff member was sacked as a result of this mishap, instead Hutt put out a press release to the effect that the roses had fallen prey to a fungus disease and that the plants had been removed to the Berhampore nursery for treatment. In reality, they all went to the tip and Hutt ordered new ones planted.

Fig 9: Rosina Ann Norwood, 1930s. Photo – S.P. Andrew. Alexander Turnbull Library reference ¼-019953-F.

Hutt’s original project for a Rose Garden and Begonia House was completed in 1960 and 1961. The Begonia House was built in 1960, stimulated by a donation of £20,000 pounds from Sir Charles Norwood, and it opened on the 22 December that year. In 1961 the pergola, the zig-zag and brick walls up to the present Herb Garden were built. All in all, even in a climate of post-war affluence, it had taken Hutt 14 years to see his project through to the end.

The surroundings of the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House were given their final form on the eastern side in the early 1970s. In May 1970 the children of Sir Charles and Lady Norwood gave $50,000 dollars towards this project. Between September 1970 and May 1971, the cut banks on the eastern side were hidden by tons of soil, and the waterfall, summerhouse, pond, and brick walls were built, supervised by assistant director Richard Nanson. As part of the project, access from the Weather Office was upgraded, and the pohutukawa along Salamanca Road were thinned and repositioned back from the road. The Begonia House was completed when the Lily House was built in 1989, a project supported financially by Sir Walter Norwood.

In the 1960s, the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House were used as a place for perambulation and viewing, rather like visiting an art gallery. Certain proprieties were expected – no rowdiness or drinking, and certainly no dogs or children in the fountain pool. All of this began to change in the 1970s. By the late 1960s, the Beautifying Society and Horticultural Society had gone, and with them much of the community that had supported the project in the late 1940s. Social and cultural conditions were changing, and new and more “exciting” uses for the Rose Gardenand Begonia House were demanded. From 1969, and through the 1970s, the Rose Garden was floodlit during the summer, and this was combined with musical and dramatic events. This use in summer was extended especially during the Summer City festivals that were inaugurated in the summer of 1978/1979. These events, which drew thousands of people, benefited from the Government funded Project Employment Programme (PEP), inaugurated under the Muldoon Government (1975-1984) schemes that subsidised artists, actors, and designers. Spectacular events were staged in the Dell and Rose Garden, and elsewhere in the city. The Rose Garden and its surroundings often looked like a fairground, and by the early 1980s children had certainly claimed the fountain pool.

Today the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House remain the most visited part of the Botanic Garden. They and the surroundings stand as a fitting memorial to Sir Charles and Lady Norwood and their family who have for over fifty years supported the Botanic Garden, and this area in particular. I also think that in some way this part of the garden should be publicly associated with Edward Hutt.

The formal rose garden

Displaying roses in a formal setting did not originate in New Zealand, and I think that it is of some interest to know where it came from, and why Hutt may have chosen it. It could be argued that a more informal layout might have better suited the site and its surroundings. I have always felt that a formal garden of this size in the Wellington topography is something of a wonder – a triumph of mind over matter: of culture over nature.

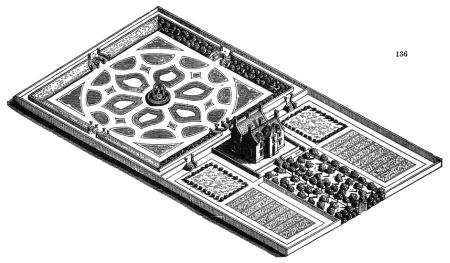

To understand the origins of formal gardens as they existed in the first half of the twentieth century, and specifically formal rose gardens, I’m going to start with nineteenth century England. By the early nineteenth century there was a reaction against the classical landscape gardens of the previous century. In the gardens of the eighteenth century, great houses, framed by trees, sat in vast lawns that swept up to their walls. This reaction, often associated with Humphrey Repton, argued that the garden should be an extension of the house, a place to use, and like the house, a product of artifice and the quirks of the human imagination, rather than a proposed improvement on Nature. By the 1830s and 1840s this had developed into a full-blown revival of Renaissance-styled formal gardens, their elaborate parterres full of the new half-hardy seasonal annuals.

To translate such styles from the gardens of the very rich to the lesser estates of the new middle classes writers like John Claudius Loudon produced encyclopaedic publications which included plans to suit a wide range of pockets. (Fig 10) The practice in the formal garden was to have the house raised on a terrace overlooking the garden, which was also surrounded by raised walks. This enabled the design to be seen as a whole as well as entered for closer inspection. Though roses were displayed in formal settings before the 1880s, the short flowering period of old roses meant that such formal gardens were established outside the main axis of the garden, where they could be ignored while they were out of season.

Fig 10: Plan for the layout of a villa residence of two acres, within a regular boundary, in the geometrical style. An illustration from Loudon’s The Villa Gardener… (London: W. S. Orr and co., second edition, 1850).

This sort of formal gardening was the cause of another reaction in the late nineteenth century, associated with the names of William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll. Robinson proposed a move away from formally planted gaudy displays of annuals to a garden composed of native British plants and hardy exotics which included such informal features as meadows of wild flowers and grasses. Jekyll took Robinson’s ideas and advocated a garden of formal and informal elements, including carefully colour-coordinated plantings of herbaceous borders, allegedly derived from the cottage gardens of England. There was much of the national ideal of “England’s green and pleasant land” in this movement. It went with the revival of arts and crafts. This involved the construction of buildings based on seventeenth and eighteenth century originals, the colonisation by urban middle classes of decaying villages on commuter networks, the collection and recording of traditional folk songs and dances, and a sense of nostalgia for an old lost England.

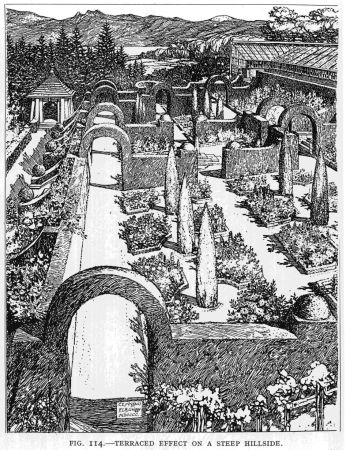

This sense of nostalgia for things old and “native” informed the revival of formal gardens during the 1890s and 1900s. This revival was based on surviving seventeenth century gardens that were originally inspired by French and Dutch formal gardens. But by the late nineteenth century such survivals were read as being native and British in contrast to the formal gardens of the 1830s and ‘40s. These had been imitations of exotic foreign styles. This development was not entirely separate from the Robinson/Jekyll type of garden, but is notable for the use of topiary, either in clipped hedges forming a series of rooms, or as in the seventeenth century gardens, quirky fanciful sculptural forms. (Fig 11) Ironically, one of the greatest of these new formal gardens was constructed not in England, but in New Delhi, India. Sir Edwin Lutyens, planner and one of the architects of the new imperial capital, designed for his Viceroy’s House (now Rashtrapati Bhavan), a large formal garden which synthesised English and Moghul ideas. Lutyens’ plan includes a large circular formal garden for flowers.[1]

The importance of this development for rose gardens was that it happened at the time rose breeders were producing perpetual flowering hybrid tea roses. By 1900 these varieties were widely used, and because of their long flowering period, the Rose Garden moved into the main axis of the garden, or, especially in public gardens, became a feature in its own right. The architects and designers of this new type of formal garden also used the pillared pergola, and often the formal Rose Garden was partially, or completely surrounded by such a structure.

One of the well-known practitioners of this sort of formal garden was Thomas Mawson, whose book The Art and Craft of Garden Making went through five editions between 1902 and 1926. Copies of Mawson’s book are held in the Wellington Public Library and the National Library in Wellington. In it are illustrated spectacular layouts for formal rose gardens, both for public parks as well as private clients. (Fig 12) The pergolas surrounding the Lady Norwood Rose Garden are simplified versions of pergolas illustrated in Mawson’s book, with their elaborate beam-work in an arts and crafts/Japanese style.

David Tannock in his Manual of Gardening in New Zealand published in the late 1920s, refers to the popularity of pergolas, rose gardens, and rockeries. Christchurch based landscape gardener Alfred Buxton spread them around the station homesteads of New Zealand between 1900 and 1930. (Fig 13; Fig 14)

Fig 11: Formal garden designed by Charles Edward Mallows. In Thomas Mawson’s The Art and Craft of Garden Making (London: Batsford, fifth edition, 1926), figure 114.

Though not all formal rose gardens were circular, judging from Mawsen’s plans, circular designs, or designs with strong circular elements were common. Tannock illustrates a circular design lifted from James Young’s book on rose growing in New Zealand published in 1921. (Fig 15)

Edward Hutt grew up and trained as a gardener when this approach to garden design was contemporary, and widely admired as “the English Garden.” To me it is no surprise that his Rose Gardenwas a late version of this received manner for displaying roses that, by 1947, was already established in other public gardens in New Zealand. His public would also have recognised his intention. The revival of formal gardens and the herbaceous border had had an impact on suburban gardens in the 1920s and 1930s, here as in Britain.

Fig 12: Rose and lavender garden for Blackpool Park designed by Thomas Mawson. In Mawson’s The Art and Craft of Garden Making (London: Batsford, fifth edition, 1926), figure 160.

Fig 13: Laurel standing at an entrance to the pergola, Greenhill homestead near Hastings, Hawke’s Bay, October 1921. The pergola and roses were added to the Greenhill garden by Alfred Buxton in about 1919. Photo – Harold Hislop. Alexander Turnbull Library Reference PA1-o-228-20-1.

Fig 14: John A MacFarlane and Jean Williams in the pergola of the garden of “Ben Lomond,” a house on The Hill, Napier, Hawke’s Bay, October 1921. Macfarlane owned a sheep station with the same name as the house. It is likely that this is also a Buxton installation. Photo – Harold Hislop. Alexander Turnbull Library reference PA1-o-228-27-1.

Fig 15: Rose Garden plan by James Young illustrated in David Tannock’s Manual of Gardening in New Zealand (Auckland: Whitecombe and Tombs, no date), figure 255.

Conclusion

Though the scale of the Lady Norwood Rose Garden gives it an openness more in the spirit of the earlier Renaissance revival formal gardens, this is appropriate for a garden, the function of which is public. (Fig 16) On this scale the pergola defines the boundaries rather than encloses the space. Over the last 20 years the complex has aquired a herbaceous boarder running along the front of the Begonia House, and the Rose Garden is now flanked by beds edged with clipped box. In 1990 the then director, Richard Nanson, proposed extending the garden with a formal planting across the eastern half of Anderson Park. This would have given the Rose Garden a larger context and strengthened the link with the Bolton Street Cemetery that is run as part of the Botanic Garden and contains a collection of old roses. Protests from community sports groups prevented this from happening, but it is an idea that may be only shelved for now. As a consequence, the Rose Garden and Begonia House remain as a formal architectural entity complete in themselves, but linked to no larger pattern in the Botanic Garden, a characteristic shared by the Carrillion and museum building stranded on Mount Cook, as well as the Railway Station.

Fig 16: Lady Norwood Rose Gardenand Begonia House from the air, ca 1965. Photo – The Evening Post.

[1] I have never come across any evidence written, printed or photographic indicating that formal gardens of any note were established in New Zealand between 1900 and 1930. Even though Rupert Tipples states that Buxton’s draughtsman, Edgar Taylor, was influenced by the British architect and garden designer C.E. Mallows, apart from pergolas, I have never seen a Buxton garden that looked remotely like the sophisticated formal gardens designed in Britain between 1890 and 1930. However, through the good offices of Google, I have discovered two gardens of quality in New Zealand, both relatively modern, that draw on the British and European formal garden. One is Miles Warren’s garden at Governors Bay, Banks Peninsular that looks very like a late nineteenth/early twentieth century English formal garden complete with clipped hedges, topiary, a rose garden, and herbaceous boarders. The other is Richmond Garden at Carterton in the Wairarapa, designed by owner Melanie Greenwood. This is in a European tradition suggestive of France, and is notable (judging from the photographs) for its absence of flowers. It is also associated with a topiary nursery and this suggests to me that there may be more formal gardens in the New Zealand countryside lurking at the ends of long private drives.